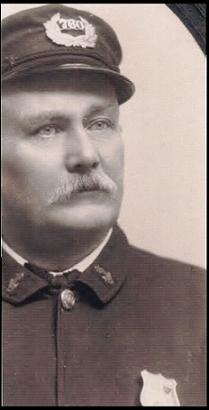

Commissioner Charles D. Gaither

"The General"

It's no secret among those that know me; I am not a fan of General Gaither, the man, that said even a broken clock is right twice a day and Gaither did some good things. So while I will never be a fan of him the person, I have to credit the thing he did right, he invented systems to make police service faster before radios were in use. He worked on a better traffic light system, crosswalks, and many other services, and devices to make Baltimore safer and better. But his racist views on African Americans and their ability to police in Baltimore were inexcusable, and while I will not ignore the things he did right, they will not give him a pass on the significant errors on his part when it came to humanity, and caring about all men, all women and all children on an equal playing field.

I had a close friend that said he himself was brought up by a racist family, so he had racist views. While he once felt the way all racist do, those views changed when he was educated and learned everything he had ever been told was wrong. He said he could understand and see where Gaither was coming from; he basically, said as kids we might have been raised with racist views and could believe everything we are told, but the day you find out they were wrong, and that the only difference between a white man and black man is the color of their skin, but you continue to have incorrect views, prejudices etc., ignoring facts that are right in front of them; well that is a racist. My friend has passed away, but he told a story of desegregation within the department and how his sergeant told him to report his new partner for sleeping on duty and he would have him fired. For the first few days he was trying to catch his partner sleeping so he could carry out his sergeant's wishes, but by the end of the first week he realized something that he was ashamed at his age for not already knowing, and by the end of the second week the two partners had done what most police partners do; they became friends. Becoming friends, they did what friends do, they attended each other's kids graduations, and weddings, they camped and vacationed together; they were true friends, brothers that our police family becomes. After saving each other's lives and counting on each other to keep protecting each other. Gaither, would never learn this kind of friendship because he was too ignorant to want to learn, the only race any of us should care about is the human race and to hate a man, woman, or child simply because their skin doesn't match yours is not only racist, it is foolish. The color of our skin is no different than the color of our eyes, and we would never dislike someone for having blue eyes when we have brown eyes, that would be silly, and while racism is no laughing matter, it is a silly person that waists their lives hating someone they don't know anything about, other than their skin is a different color. Having done so his entire life, caused Gaither not only to lose the respect of historians that would someday study his work as a police officer, but it put a dent in that chapter of Baltimore Police History.

Something all commissioners need to take into consideration is that the job they take on when they take the oath as a police commissioner is more significant than they are and that knowledge has to become part of the choices they make.

Gen. Charles D. Gaither

Baltimore City Police

Commissioner (1920-1937)

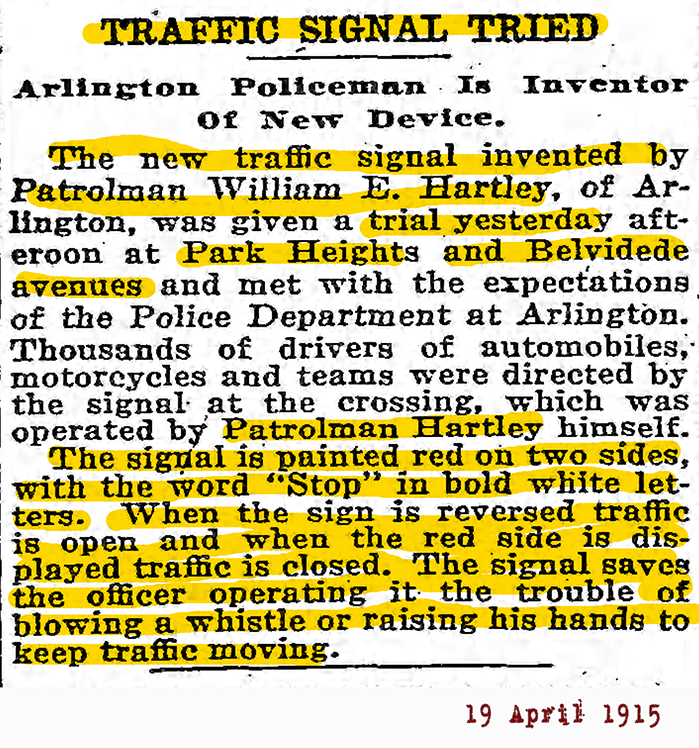

On June 1st, 1920, a man by the name of Brigadier General Charles D. Gaither, previously commander of the First Brigade, Maryland National Guard began his duties as the Governor-appointed first Baltimore City Police Commissioner. Called "The General," he took Baltimore City traffic seriously and would personally drive through downtown city streets observing the manner in which traffic was handled, especially during rush hour.

By July 1921, under his direction, the Police Department placed fourteen six feet high "lighthouses" on concrete bases which were intended to warn motorists of dangerous curves and bends at night. The flashing lights in the lighthouses were fueled by acetylene tanks (see photo, below and left) - red flashing indicated places where people had been killed, yellow for dangerous curves or bends where caution must be exercised, and green was for danger at intersections where slow, careful driving should be exercised to the right.

The earlier days of traffic lights and warnings resulted in disgruntlement by drivers and even beasts. Prior to placing the traffic lights on streets with protective bases, they were continually run over by motorists refusing to stop. On October 16, 1923, the Baltimore Sun reported that a certain Jersey bull by the name of Reddy had created a riot in the middle of the congested intersection of Bryant and Pennsylvania Avenues while being led to slaughter. A heard of 40 bulls were being driven down the avenue where automobiles stopped in obedience to a blinking red light, but not Reddy who saw it as a challenge and proceeded to charge it. In the charge, a truck struck and broke its leg before he could reach his "enemy." Unfortunately, agents of the SPCA needed to kill the Reddy earlier than his originally intended fate.

4 May 1921

Police Reorganization

Whether or not all citizens will be able to subscribe to the details of Commissioner Gaither has a plan for reorganizing the police department of Baltimore, there should be general satisfaction over the fact that he has seen fit so far in advance of the meeting of the legislature to prepare a program. The trouble with so many a virus state and municipal as visuals is that they wait until the last minute, and then wonder why the public does not at once jumped to support their half-baked ideas. It is comforting to know not only that Commissioner Gaither is alive to the present need for a reorganization of his department, but that in the drafting of his proposals he has looked ahead to the steady growth of the city.

That Baltimore is at present under-policed has frequently been contended by the commissioner and others. That the present organization is a clumsy one and not calculated to produce efficient work is becoming increasingly manifest. In some respects, at least, Mr. Gaither has adopted for his program ideas which have proven effective in other communities. It is gratifying that he has thoroughly prepared himself to discuss the subject publicly. If the people of Baltimore are not in substantial agreement as to what they want by the time the Legislature meets, the commissioner at least, will not be to blame. He has started the discussion.

Transfer of Badge to Mark the Retirement of General Charles Gaither

1 June 1937

William P. Lawson will take over the office of Commissioner of Police for the next six years at noon on Tuesday 1 June 1937.

General Charles D. Gaither at noon on that same Tuesday 1 June 1937 was to hand to Mr. William Lawson the gold-plated commissioner’s badge which he had received 17 years earlier from Mr. Lawrason Riggs when General Gaither himself became Baltimore Police Department’s first solo Police Commissioner.

By this act, Mr. Lawson, who took the oath of office a day after his appointment by Gov. Nice, automatically entered into his duties as the executive head of the Baltimore Police Department becoming the agencies’ 2nd solo commissioner a title he was expected to hold for at least the next six years.

Has Name Taken Off

Several days earlier General Gaither gave his badge to Mr. George J. Brennan, Executive Secretary of the Department, with instructions to, “Have my name taken off and Mr. Lawson’s put on.” No one could recall if Mr. Riggs’ name was removed 17 years earlier when General Gaither was to receive the badge by appointment of former Governor; Albert Ritchie. Mr. Riggs was the president of a three-member police commission known as the BOC (Board of Commissioners). The BOC was discontinued when Gov. Ritchie reorganized the State Government, including the Baltimore Police Department which at the time fell under State rule.

No Formal Ceremony

Other than the transfer of the badge, there will be no formal ceremony when Mr. Lawson takes over General Gaither’s duties. In certain Republican circles, however, it was whispered that Mr. Lawson might find himself the center of a large group of congratulating friends bearing floral tributes. Previous to his appointment by Governor Nice, Mr. Lawson was chairman of both the state and city Republican State Central committees. General Gaither was at his office in the Police Building yesterday morning but left early to enjoy the afternoon on his Howard County farm. There he recalled the change that had taken place in the department during his 17-year administration.

City’s Growth of The Force

“When I Came In,” he said, “942 men were authorized for the force, but we had only 725 or 730. The Department was short of men who had a base pay of $25 a week. This was right after the World War and men could get more money in other work. Many of the members of The Police Department gave up their jobs to enter more remunerative employment.

“When I came in the only things the department had was a Detective Bureau of 25 men, and 725 patrolmen, a Bertillon Bureau and a “Beauty Squad” of 68 policemen detailed to handle traffic at street corners. Some of these were on bicycles, and there were three motorcycle men.

“Out of this ‘Beauty Squad’ was developed to present Traffic Division, with 182 men and 47 motorcycle men. We now have 1357 patrolman with a base pay of $35 a week”

Gaither Reviews Work

Now hundreds of men every year take the examinations to get on the eligibility list for appointment to the Baltimore Police Department. Pressed to enumerate some of the features he introduced into the department; General Gaither modestly agreed to name a few.

They included the following;

The Accident Bureau.

The Bureau of Missing Persons.

The Blinker Light Recall System.

The Automatic Signals.

This Through Highway System.

The Interstation Teletype System.

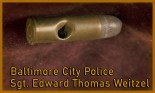

The Bureau Ballistics, Including an Arsenal for Emergency Purposes.

The Detective Bureau of 85 Men.

The Traffic Division.

Standardization of Police Arms, now all men carry .32 caliber pistols.

Removal of the Police Department Headquarters from a cramped space in The Courthouse to its own building on Fallsway.

The Radio Patrol.

The beginning of a two-way Radio Communications System, now being installed.

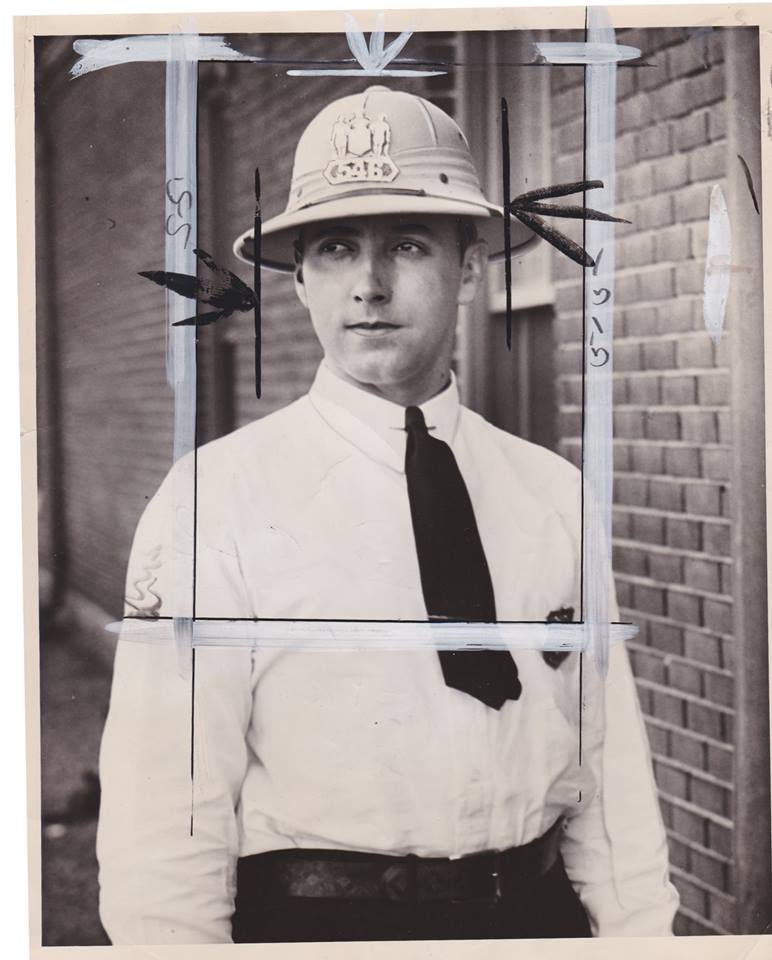

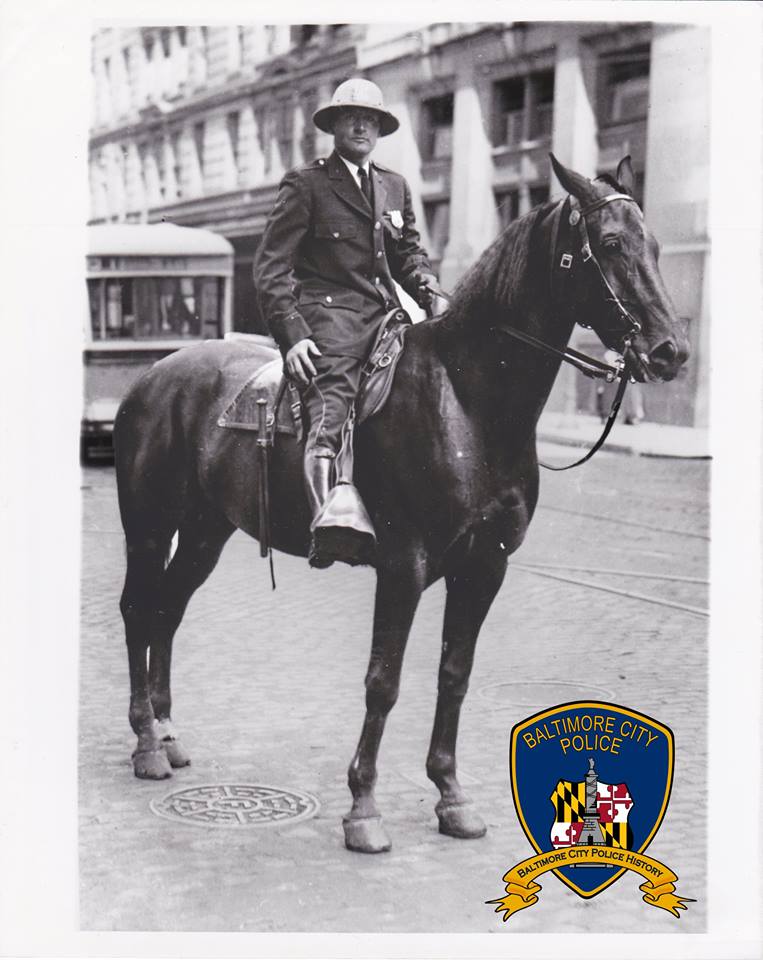

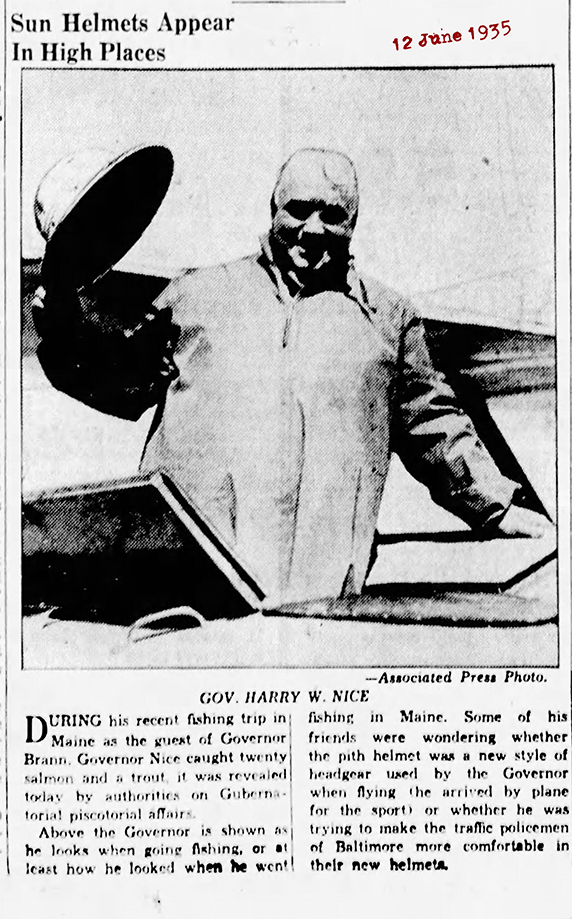

Uniforms improved

The fact that General Gaither failed to mention but which Mr. Brennan did not forget was that the General was also the department’s stylist. When he became Commissioner, patrolmen wore uncomfortable uniforms, with tall, stiff helmets. Like those worn in Lindon by Bobby cops. General Gaither designed the uniform most like to uniform worn today as what we call Class A’s. And, the general started a tradition still used to this day in which during hot summer months, police are permitted to doff their coats. Before this, police officers were to wear their coats all year round. Not only were they to wear the coat all year round, but they were also required to wear their uniform both on and off duty. One thing General Gaither did that may or may not have been seen as respectful to the men and women that had been a part of the Baltimore Police Department long before he had arrived. To those before him, and after him that had died and or would die, as well as those who had been seriously and permanently injured or someday would be for the City, the department, and for the uniform of a Baltimore Police Officer. He felt there were those that worked the streets of Baltimore and earned a right to wear the uniform of one of its Police Officers. As such General Gaither, never wore our uniform, he never felt as if he earned the right; so he always appeared no matter what the occasion, in mufti.

POLICE SOON READY WITH NEW ALARMS

5 Sept 1922

The Sun (1837-1989); pg. 6

"Recall System" Will Be Completed

In Two Districts Early Next Week.

PLANS CITY-WIDE EXTENSION

Gaither hopes to have All Baltimore Covered by Light

Signals next Year.

After delays and complications for more than six months the new police "recall system" will be completed early next week [11 Sept 1922] in the Central and Western districts, it was announced yesterday by Charles D. Gaither, Commissioner of Police. This system, conceived by the Commissioner, will be established throughout the city by next year, Mr. Gaither said, providing an appropriation permits it.

Having been tested through experiments with the call-box at Baltimore and Charles streets and in outlying sections of the Northern District, the system is regarded as feasible and satisfactory and is expected to aid in the quick capture of criminals. Through the "Recall" patrolmen all over the city can be summoned immediately and instructions were given to the entire force at one time.

How System Works

All police call boxes in the Central and Western districts are being equipped with a red light projecting over the top of the box. A cable connects with the series of boxes to the respective districts and with headquarters. When a patrolman is wanted his box is "flashed." And the light blinks until the telephone receiver is removed from the hook. If the entire force is wanted every box flashes simultaneously until answered. Under the present system, there are no means of obtaining communication with patrolmen on the street. The policemen call their respective districts every hour and between the hours of call unless someone is dispatched to call the officer wanted. There are no means of locating him. When the light flashes the officer will know that his district wants him and will answer.

City-Wide System is Good

“The plan is a good one. I think.” commented Mr. Gaither ... “and by next year we hope to have the system installed in all of the eight districts. If all of our appropriations are sufficient this will be done. We were delayed this year when we received the wrong equipment and had trouble in obtaining the correct cable. The siren system, as established in New York banks, was commended by the Commissioner. Banks in downtown New York have been equipped with huge horns that are blown in cases of robbery or hold-ups, and attention is immediately attracted to that point. The idea could be adopted here advantageously.”

Gaither suggested this program and it was not only successful here in Baltimore, but it was a system that would be adopted by departments up and down the East Coast.

“The General” of Baltimore Police

Commissioner Gaither Learned his Lesson as a Guardsman

Half a dozen spellbinder’s harangue a listless crowd of perhaps fifty persons in the War Memorial Plaza around the square stands a hundred uniformed policeman. The Officers all twirling their clubs, looking bored. Nothing happens. So many policemen, apparently on hand to preserve order, seems a little silly. They outnumber the rest of the crowd and themselves two to one. No nervous Nelly was Commissioner Charles Gaither, who sent all those bluecoats to the Plaza. But he has seen Baltimore’s police force overpowered and whipped to a standstill. During some of his first days policing Baltimore, then as a National Guardsmen, he and his men were stoned by Baltimore’s infamous "Mobtown". He helped put down the rioting in the streets of Baltimore at the point of the bayonet. This happened 60 years earlier, but he could never forget. He doesn’t believe in taking chances now. Aside from the effects, it has had on him, now it is more than just him. He has the men wearing the uniform of our Baltimore Police to consider and so he made all decisions with them in mind. Or, as he expressed it: “I don’t believe in sending a boy to do a man’s job.” That is why our police will as often as possible outnumber the crowds they are to maintain, protect and control. Charles D.Gaither was born November 20, 1860, at Oakland Manner, an 1800 acre farm on the Columbia Pike about 2 miles below Ellicott city. He was little more than a year old when the Civil War broke out. His father, George Riggs Gaither, recruited a company of Marylanders for service in the Confederate Army, and during his absence, his farm was sold by his father, who feared confiscation of all his rebel sons’ property by the Federal Government. A house at 510 Cathedral St. became the Captain’s home, from there Charles D. Gaither, the fourth of nine children, went to private schools ran with number 7 Fire Engine Company and establish a neighborhood in reputation as a first baseman. When the boy was 12 years old his father was elected Major of the Fifth Regiment, whose roster read like the societies visiting list. For in those days men paid an initiation fee of five dollars to join the Regiment, monthly dues of a dollar and $50 for a uniform. Each man also paid his own expenses at summer camp, a frolic usually held at Cape May, Longbranch or some other fashionable seaside resort.

From the day his father became an officer of the Fifth Regiment Charles Gaither began to hang around its drill hall, the present Richmond Market Armory, inpatient for his 18th birthday in order that he might enlist, in April 1877, the father, who had been promoted to Lieutenant Colonel resigned, but the son was still bent on being a soldier.

At 6:30 PM Friday, 20 July 1877, the military call, one – five – one, was rung on the City Hall and fire bells. Police closed all of the bar rooms in town. Gov. John Lee Carroll had ordered the Fifth and Sixth Regiments of the Maryland National Guard to Cumberland, where striking railroad engineers and firemen had halted train service.

In the crowd gathered at the Richmond Market Armory to watch the Fifth Regiment marked out for the former Lieut. – Col. and his son. The companies falling in were little more than skeletons. Earlier that summer dissension in the Regiment had led to the resignation of all its field officers, reducing the number of its enlisted men to just 175. Of these only, 135 had reported for duty. “Going along, Col.?” Someone asked in the elder Gaither. “Looks like we’re going to need all we can get.” Suddenly Charles D Gaither, a square-shouldered, 17-year-old boy who stood 6 feet tall and weighed clothes and all maybe 180 pounds, felt his father’s hand clap his shoulder, his father’s voice saying: “What’s the matter with his boy going?”

The younger Gaither stumbled upstairs into the armory, delighted. With his father’s consent, he was enrolled in senior Capt. William P. Zollinger’s Company H. Someone tossed the new recruit a pair of gray trousers. Someone else gave him a blue blouse. A third man slapped a forage cap on his head and a fourth put a musket in his hands.

In the absence of field officers, senior Capt. Zollinger commanded the entire Regiment. His company, age, led the column down Eutaw Street toward Camden station, where the guardsman were to in train for Cumberland. Because of his height, Private Charles D Gaither was number three man in the second rank of fours

The sounding of the military call that July afternoon, when the streets were filled with persons who were – bound from work (there were no 40 hour weeks in those days) jam that Eutaw Street with people curious to see what was going on.

At Pratt Street, the crowd cheered the soldiers. But the Camden Street they stoned them – a sudden change in mob temperament never forgotten by the tall, roll recruit in the second rank of that force.

Near the station, the crowd blocked the street. The command was: “Battalion holds! Fixed bayonets!”

The crowd broke. Into Camden station marched company H, halting just within the wide door while an officer hurried ahead to find their train.

From the rear of the column the word came up the line; “and They’re stoning them badly back there!” Camden Street was thick with flying brickbats.

The men in company H stood with their shoulders hunched, protecting their heads with the blanket roles on top they’re knapsacks. Through the station, door sailed a brick that bounced off private Gaither's blanket role, smacked the first sergeant squarely on the head and knocked him flat on his bum.

“Burn them!” Bellowed the mob in Camden Street. “Hang them! Shoot them! then Burn them”

The train that was to have taken the guardsman to Cumberland was partly wrecked by the mob, which later set fire to the station. Firemen who answered the alarm were stoned. Hose lines were cut. The police could make no headway against the mob. Alarmed by the riot, Gov. Carroll countermanded the order sending the guardsman to Cumberland, directed them held at Camden station and telegraphed President Hayes for Federal Troops “to protect the state against violence.”

Private Gaither got his first bayonet practice that night helping the Fifth Regiment clear the streets around the station, usually, a bayonet prick was enough to send a rider flying. Once the command was given, “Load, Ready, Aim”… But it was not necessary to fire. The mob did not wait. Private Gaither learned to look hard – Boiled, to appear comfortable when lying on the stone sidewalk with a knapsack for a pillow.

Business, as well as train service, was suspended next day. Banks, post office, Custom House were under special guard. A Revenue cutter covered bonded government warehouses at Locus Point with his guns. Light Street streamers anchored in the harbor to avoid damage. Railroad cars were burned. Again riders charged the guardsman. 77 members of the Fifth Regiment had been injured at the end of the second day of strike duty.

2000 United States Marines and soldiers of the regular Army arrived in Baltimore the next morning – Sunday. 2000 more were on their way.

By the following Saturday, for the first time in a week, trains began to move again. Company H of the Fifth Regiment was sent up along the main line of the Baltimore and Ohio, toward Frederick Junction, to guard railroad bridges.

Private gazers squad was dropped and Elysville, where the tracks crossed and re-crossed the Patapsco River over to bridges. The guardsman only rations were the hardtack they carried in their haversacks. They had no tents, the only shelter insight was a Flagman’s House.

“At least a place to sleep,” muttered the corporal. “How about it Gaither?”

The flagman pricked up his ears. “Gaither,” Gaither he repeated. “Howard County Gaither – Rebel Gaither – down there by Ellicott city? Not in my house!” That night private Gaither slept under the front porch.

The Police Commissioner is not sure that he really learned anything about policing during that first brief tour of duty. He was too young, too green. But he must have absorbed a certain familiarity with what mob violence means.

The sixth Marilyn Regiment to entrain with the fifth when the guardsman were first order out, never had reached Camden station as a unit. Clubbed, stoned, fired upon from all sides by the mob in Baltimore Street, the soldier had halted to wheel and fire back into the crowd several times. 10 persons were killed and 13 wounded before the Regiment was literally torn to pieces, its members were seized, stripped of their uniforms and thrown into the Jones Falls. The few who made the Camden station ran for it. Their prudent commander followed them in a carriage – after dark.

Looking back on this, the Commissioner sees the value of a demonstration of force.

The fifth Regiment had March to Camden station in regimental formation. The sixth had been dispatched from its armory, at front and Fayette Street, company by company. The companies were small. Had they stuck together, the Commissioner thinks, they might’ve spared themselves a lot of grief.

Once he came of age, young Gaither’s promotion in the fifth Regiment was rapid. By 1887 he had been elected Connell. Three years later he resigned to give all his attention to a bond brokerage business. But shortly before the United States declared what John hay called it “splendid little war” with Spain, the formal Connell was persuaded to rejoin the Regiment as Capt. of company F. He was still Capt. of company F in May 1898, when the Regiment went South in Cal high boots, flannel shirts and winter overcoat’s to fight mosquitoes, bed cooking and typhoid fever at Tampa. Here is men began to call him “big six.” Nobody knows just what inspired this nickname.

For 10 hot weeks the Regiment, now designated the fifth United States volunteers, set around Tampa was sweat in its years and sand in his mouth. “Big sixes” company was detached as division headquarters guard. Orders were issued to embark the whole Regiment for Cuba – orders were countermanded. Santiago. Typhoid swept the fifth. It was mustered out of the federal service and shipped home.

But the martial spirit was still upon the captain of company F. Through the United States Sen. Louis Emery McComas he applied for a commission in another volunteer Regiment. Sen. McComas carried his request to the White House and pressed upon Pres. McKinley that the applicant was the son of a former Confederate officer.

“A Confederate officer's son?” Mussed the President. “Would he accept a commission in a Negro Regiment?”

He would and did, going to Cuba as a Lieut. of the ninth United States volunteer infantry, a Negro outfit. He remained in the federal service until 1899, then returned to Baltimore to succeed his father, who had died that year, as commander of the fifth Regiment veterans court with the rank of Col.

After the Baltimore fire, Adjutant-General Clinton L Riggs made Col. Gaither inspector – general of the Maryland National Guard.

The acting Inspector General told Marilyn’s guardsman how to drill. As executive officer as Saunders rains later he also taught them how to shoot. He himself was Capt. of the American rifle team that won the 1912 international match at Buenos Aires.

Appointed Brig. Gen. in command of the Maryland National Guard in 1912, his first active duty as a general officer, like his first active duty as a private soldier, was riot duty. He had four companies of the Fifth Regiment to Chestertown to bring the Baltimore to Negroes in danger of being lynched.

There was no evidence. A clever show of force was all that was necessary, general Gaither said afterward. If you are ready for trouble and look as if you mean business, trouble is not likely to begin. That is one of his pet theories

A high rating awarded general Gaither in a tactical test against regular Army officers on the Mexican border in 1916 seemed to assure him of going overseas as a brigadier when he took the Maryland brigade to Camp McClellan at Anniston the following year. But early in December, he suffered the keenest disappointment of his life. An army surgeon listens to his heart, ordered him discharged for physical disability.

In vain to the general appeal for a revocation of his order. A hard rider, a strenuous tennis player, he had never been in better health. But the order for his discharge stood and at Christmas time he came back to Baltimore, his faithful sorrel, Picket, following in a boxcar.

From a reviewing stand at the day, the Maryland National Guard returned to Baltimore from France the general stall picket dancing to the music of the band – with a policeman in his saddle. Picket had already joined the police force. Before the war was over the general had sold him to the mounted service.

Such was the preparation of the man appointed in 1920 by Gov. Ritchie to be police Commissioner of Baltimore. He came to the job 60 years old, but a vigorous, a wrecked, military man with a soldiers jaw, a stick and a pipe and a soldier’s vocabulary.

The day after his appointment the general (he is always been “the general” to the police) announced that the day of “pull” was over as far as the Police Department administration was concerned. The cops squared their shoulders, saved a little closer, put a little more polish on their shoes and a sharp increase in their trouser and waited for the lightning to strike.

No shakeups, no dismissals followed. And when they got to know their new boss they got to like him. In believing any of them were perfect. He told them so. But he was ready to go to bat for them. Out of this devotion of the general for his force grew a police esprit de corps never before particularly evident here.

The general had no fool’s idea – his own phrase – about policing. For all the tradition of snap and cadence behind him, he was far from being a martinet. He didn’t believe that method or system can substitute for common sense. More police and speedy trial answered the crime problem for him.

He knew the town from end to end – and from a tired flatfoot’s point of view. For years he had been walking to keep down his weight. He knew how long it took to walk any beat in the city, the quickest and straightest route between two given points. He is still a great walker, frequently turning up on the remote post to ask astonished officers what is happening. Prohibition and traffic were the Scylla and Charybdis of the first years of his administration. Crime, with the exception of the Noris case, took a backseat. A ruling by the attorney – general relieving police from enforcing the Volstead law called for some rather delicate discrimination. And no traffic regulations that suit everybody having yet been perfected, the general got it going and stopping when he told motorist what they could and couldn’t do.

But he is never been swept off his feet by any crusading zeal. He figures that enforcing the law – was he knows to the letter – is a much more important police function.

If his men smother radical demonstrations before they have time to sprout, they are likewise in order to play fair. In labor disputes, he never forgets that strikers have their rights and demands that his men work and partially to preserve order. Family relief work by police during the first critical emergency of the depression, to say nothing of food and shelter provided until around 5 o’clock in the afternoon – except when the horses are at Pimlico. He likes to see them run, Homeless men at police stations, have made his department the first friend to every afternoon of the spring and fall meats, but rarely places a bet because he picks too many wrong ones. He telephoned headquarters every night at 11 o’clock to see what is up and tunes into police calls. Needy.

The General makes his job a full-time one, getting down to work at 9 o’clock every morning and staying there without any time wherever he goes, and occasional football or baseball game on a Saturday afternoon, Pimlico during the racing season the theater at night, the general always buys a ticket. Since he became police Commissioner he has never been known to accept a pass. And it is most uncommon for him to use a Police Department automobile. When he rides, he rides in his own car, buys his own gasoline. He would rather walk and ride any day.

Now 75 years old, his hair snow white, he is given up to set or two of 10 as he used to play every summer evening before dinner was one of his two daughters. But he can still walk the legs off of many of the younger man. Fine mornings, from early fall until late spring, see him strolling down to the police building from his apartment at Preston and St. Paul streets. When summer comes he and his wife move out to a farm on high rolling hills near Ellicott City.

Why should he be popular in the police department? If he has done nothing else, he has put all the cops on a three platoon system, which means less work, and raises their pay. But the administration is mutual. After 15 years as commissioner, the general says”:

“It takes nerve to go into the places that a policeman has to go. But my men go in. None of them has ever been yellow.”

This is the one thing that has caused a loss of any possible respect I could have this commissioner. I would have liked some of the things he had done, helping to cover the paychecks of the entire police force once the for some reason the city's check would not or could not be cashed, this commissioner withdrew the funds, sent them to the district's captains and saw to it that is men were paid. He invented systems to make police service faster before radios were in use, worked on a better traffic light system, crosswalks, and many other services, and devices to make Baltimore safer, but his racist views on African Americans are inexcusable and while I will not credit away for the things he did right, they will not give him a pass on this major error on his part when it comes to humanity caring about all men, all women. I had a close friend that said he was brought up by a racist so he had racist views and while he once felt the way all racist do, those views changed when he was educated that everything he had ever been told was wrong. He said I can understand and see where he was coming from; he basically, said as a kid we might have been raised with racist views and could believe everything you family told you, but the day you find out they were wrong, and that the only difference between a white man and black man is the color of their skin, and you continue to have the wrong views, prejudices etc, ignoring facts that are right in front of you; well that is a racist. My friend has passed away now, but he told a story of desegregation and how his sergeant told him to report his new partner for sleeping on duty and he would have him fired. For the first few days he was trying to catch his partner sleeping so he could carry out his sergeant's wishes, but by the end of the first week he realized something that he was ashamed at his age for not already knowing, and by the end of the second week the two partners had done what most police partners do; they became friends. Become friends, they what friends do, they attended each other's kids graduations, and weddings, they camped and vacationed together; they were true friends, brothers that family police become after saving each other's lives and counting on each other to keep protecting each other's lives. Gaither, would never learn this kind of friendship because he was too ignorant to want to learn the only race is the human race and to hate a man woman or child simply because their skin doesn't match yours is not only racist, it is foolish. The color of our skin is no different than the color of our eyes and we would never dislike someone for having blue eyes. Having done so his entire life, caused Gaither not only to lose respect of historians that would someday study his work as a police officer, but it put dent in that chapter of Baltimore Police History, something all commissioners need to take into consideration, the job they take when they take the oath as commissioner is bigger than they are and more important too.

3 July 1920

No Negro policeman, General Gaither’s dictum –

Announces none will be appointed, even if they pass examination declares time is not ripe representative of color race informed of decision – can maintain order without them, Commissioner Rules.

Police Commissioner Charles the Gaither has decided that Negroes although they take the examination, will not be appointed to the police force.

General Gaither declared yesterday 2 July 1920, that “the psychological time had not come in Baltimore for the appointment of Negroes on the force.”

The Negro population was informed of general Gaither’s stand through a Negro newspaper. Call Murphy. Colored editor of the paper.: General Gaither Tuesday and asked for the generals “position on the subject of appointing colored men to the force providing they were successful in passing the police examination and that their names were entered on to the eligible list.”

The general told Murphy the time had not come for such action and that he positively would not appoint a colored man as a member of the department. Murphy appointed out that New York City was a force of nearly 11,000 policemen at eight Negro policeman. General Gaither replied that if the same percentage were applied to the local department Baltimore would have no Negro policeman.

“There is no doubt,” said Gen. Gaither. “That colored policeman could be of value to the department under certain conditions, but Baltimore does not need Negro policeman at this time. Our officers and patrolman have for many years maintain law and order in Negro neighborhoods and we propose to do so in the future. As far as I am concerned the question of appointment of Negroes to the police force is settled.”

Colored men interested in having Negroes appointed to the force made an appeal to the former police board headed by Gen. Lawrason Riggs. At that time information was submitted showing that the following cities had Negro policeman: Pittsburgh 65 Trenton to Philadelphia 300 Cincinnati nine Chicago 95 New York eight Los Angeles 18 Cleveland 15 Detroit 14 Indianapolis 15 in Boston 25

Figures were also submitted showing the cities that did not employ colored policeman. The large southern studies not having Negro policeman New Orleans and Atlanta. Gen. Riggs told the Negro delegation then that he did not think the time had come for the appointment of Negroes to the force.

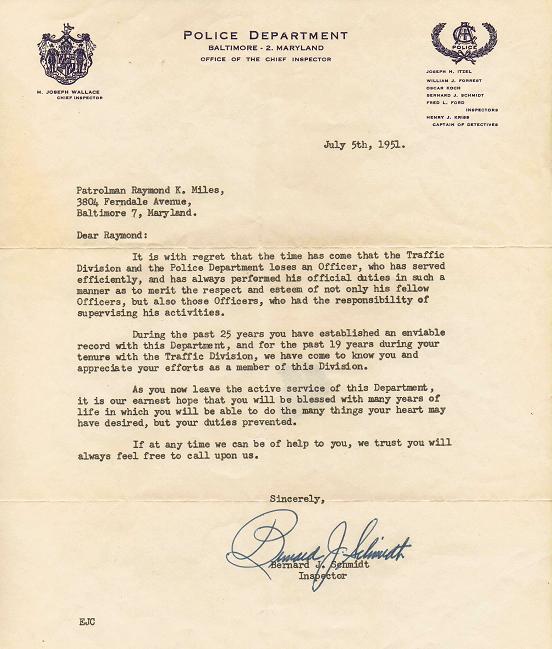

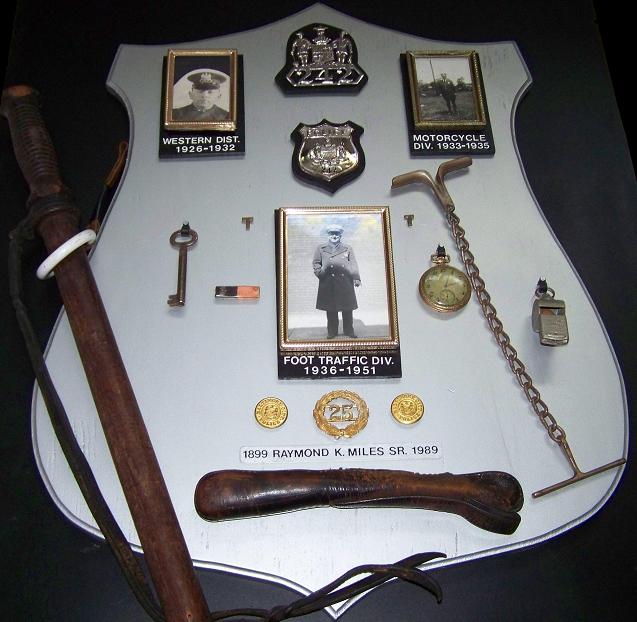

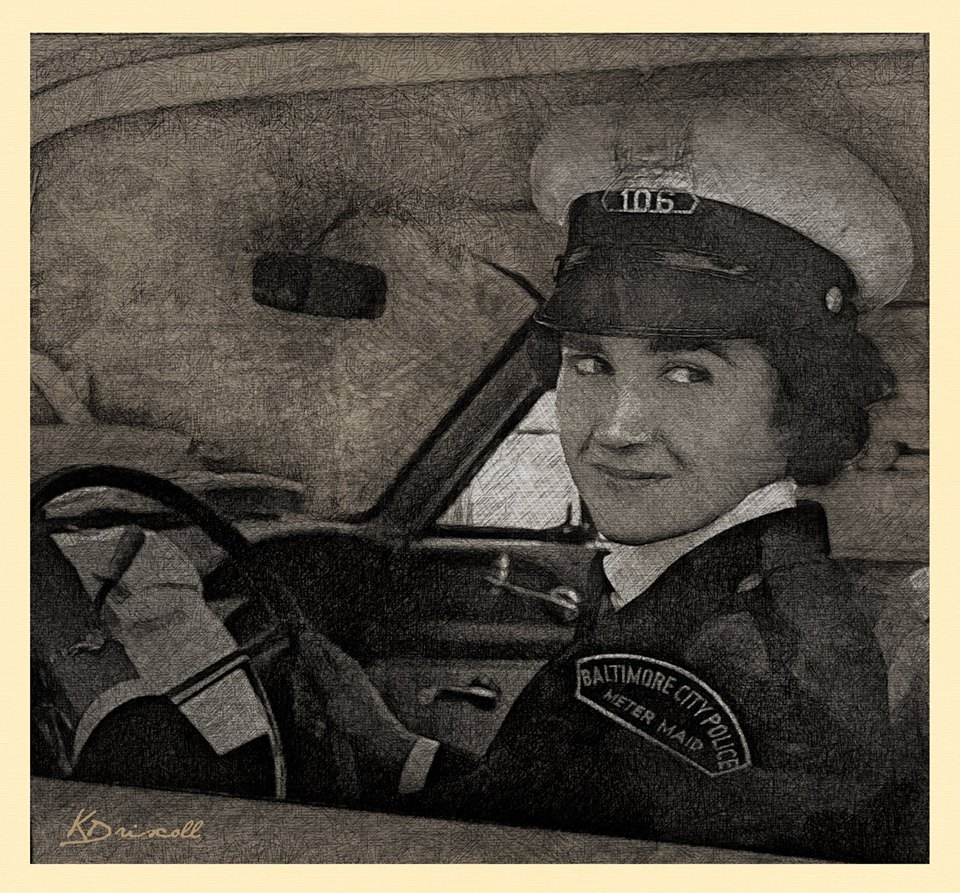

4 December 1937 - Mrs. Whyte, become the First Negro Member of Force, she was hired and assigned to the Northwestern District… she would continue to work for the Baltimore Police Department until her retirement 3 December of 1967… during her 30 years, she never missed a single day. In 1955 she was promoted to the rank of sergeant. She was in charge of the policewomen and transferred to the newly opened Western District. In October 1967 just two months before retirement she was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant. Charles D. Gaither, was Police Commissioner of the Baltimore Police Department for 17 years, from 1920 to 1937. There are those that dislike the racial tension that was once a part of the Baltimore Police Department, and while some may say there are still racial problems, we all must admit, that in 1920, while qualified for the Job, Mrs. Whyte would not be hired because of policy and a Commissioner that publically stated he would not hire a Black officer. Any issues of today, are matters of personal problems, maybe a sergeant, or squad member, but today we have the policy on our side, a side that is right in not holding someone back from doing their job, due to skin color. When Mrs. Whyte was finally hired, she showed everyone what education and persistence can do for a race.

Restless Use and The Call Of The Road

17 August 1924

Bill and Jim were “hard guys” they read all the “Wild West” stories they did find, and they never missed a movie in which was pictured the wild West. They would discuss their desires to “go West and grow up with the country.” Mutually agreeing that such an existence would be “life.”

The respective families of Bill and Jim didn’t know they were “hard guys,” in fact, they thought them normal boys who didn’t wash their ears as often as they should and two were given to yelling when grown-up people talked and will be modulated tones. The families above agreed that boys of 14 and 15 years old were “trying.”

When Boys Disappear

Then one day Bill and Jim disappeared, and their families were astounded. Of course, they knew about the boys taste for the wild West fiction and movies, but they had never taken it seriously. However, the best thing to do seemed to be to send a request to the police headquarters in nearby cities, giving a description of Bill and Jim, and asking that they are sent if found back to their home in Western Maryland.

One of these notifications came to Baltimore police headquarters; it was sent to the Bureau of missing persons, of which Capt. Joseph McGovern is chief. The names and descriptions of the boys were put on the “lookout.” Which every member of the police department receives: and Sgt. Edward Doherty, who special work it is to look after runaways, added the task of discovering them to his list of responsibilities.

A few days later two small boys were located sleeping on benches in one of the squares in Baltimore. They acknowledged that they were the intrepid seekers for adventure. Bill and Jim, emphasized that they were very hungry, and exclaimed, “G but will be glad to get home!”

This story is typical of the many that come to the Bureau of missing persons and to the office of the traveler's aid society as well. Both organizations devote much of their time to the problem of the runaway boys and girls. According to officials of both, the problem of the runaway girl is more difficult than that presented by her brother.

“Sometimes I think that running away is a part of a boys education,” said Mrs. Mary C judge, executive secretary of the traveler's aid society. “Although we are supposed to look after the girl traveler especially, we also keep a watch for the boy who may be in need of assistance: and we are called upon quite often to help some runaway youngster who doesn’t find his freedom the fine thing he expected it to be.

“Of course, there are various reasons why both girls and boys leave their homes, but it is seldom that we find a boy who is sorry to be located and returned.

“With the girl, there is always more difficult, as the average runaway girl is usually a social problem, her case is likely to develop tragic elements, and she has left her home because she cannot bear to face disgrace.

“But, behind the boy's flight there may be any number of reasons: and in the majority of cases, his act is only indicative of a passing phase.

“One of our representatives noticed a boy and Union Station a short time ago, who, one question, acknowledged that he had run away from home.

“At first he gave a fictitious name, but later told us the truth and asked us not to notify his mother. He had been working, he explained and earned six dollars a day, although he was only 17 years old: but he had a quarrel with his mother and decided to leave.

A Case In Point

“He told us candidly that he was sorry, but said that he didn’t want his family notified as he intended to get work and earn his Fairholm.

“However, despite his request, the fact that he was a minor made it advisable that we Institute a discreet inquiry as to his family, which we did through our representatives in his home city.

“Through them, we ascertained the home conditions were splendid and that the boy's return was greatly desired.

“The story ended by the mother wiring the fair and the youngster gladly coming back. We had a report on the case the other day stating that the boy is again at work and everything is progressing well.

“The desire to see the world is reasonable for many boys leaving home. When a young fellow grows to be about 14 to 16 years old, he wants to broaden his horizon.

“But that is a desire that doesn’t die with age,” continued Miss judge. “For the oldest runaways we have had under our jurisdiction was 87 years old. He was an inmate of a country home in the western part of the state and decided that he wanted adventure. So he came to Baltimore with a roll of bills and two trunks: but he wasn’t very well able to take care of himself, so we had to send them back.

Thought to Try Bayview

“Another case that had an element of pathos was that of the runaway woman more than 70 years old. She had been in a charity institution in Washington but decided she didn’t like it there.

“I heard Bayview was a fine place,’ she told us, in the country where you get butter and eggs. So I thought that, if I had to be in a poor house I’d rather be in Bayview.”

“So you see,” continued miss judge, “the wanderlust doesn’t strike only the young people.”

Miss Judge instances several 13 or 14-year-old girls who have started out with the idea become a Mary Pickford’s, but who have been returned to their homes.

Stepparents As Causes

At the Bureau of the missing persons Sgt. Doherty added a few reflections on his experience.

“The reason the youngsters leave home?” He repeated an answer to the question. “Well, there are a number of reasons.

“When a boy is about 15 or 16 years old he may not have any better reason than that he just wants to get out and see the world – and occupation of which he is quite likely to tire in a very short while.

“However, sometimes a boy leaves home because of unhappy home conditions, and one of the causes that stands out is the stepmothers or stepfathers. You see, a mother or father may flush with the child all day, or the child may do the fussing, and no real harm may be done: but just as soon as the stepmother or stepfather do the fussing one may look for trouble.

“Of course, motion pictures showing the “Wild West,” not as it is but as boys like to think it is, have a great deal to do with the reckless spirit that takes hold of a lot of young fellas, but I think another important contribution to this spirit, especially in girls, is the literature that pictures a certain sort of life as if it were filled with luxury and entertainment.

“I don’t think that telling the story of a woman who has broken all social and morals, but who finds life gilded for her, is at all helpful. The silly young girl with think that if she runs away and goes in for that sort of life she, too, will achieve luxury and wealth.

“You’d believe this as sincerely as I do if you could hear them talking about certain famous – or somewhat infamous – characters. I’m sure that this sort of story has a lot to do with many of girls determination to get out and see the world – a determination that always ends in grief.

Finding Girls Difficult

“Girls are more difficult to locate than boys, because the average boy runs away ‘on his own,’ while the girl often has an older or more experienced mind to guide her. Usually, the reason for a girl’s disappearance is ‘an affair’ with some man.

“But the boys just run away for the excitement, or for the adventure and pretty nearly always they are delighted to be ‘picked up.’ The average youngster may bring a few dollars away from home without, but that gives out very soon, and then he is ‘up against it.’

“Just the other day I found a boy who would come to Baltimore and put up very grandly at one of the hotels until his money had exhausted; then he began to wander the streets, hungry.

Nearly All Boys Found

“We find almost 95% of the runaway voice; and unless they are afraid of punishment or perhaps proud, they’re pretty glad to go back to three tasty meals a day and comfortable home.

“This applies more particularly to the boys of good families of who may fall victim to “the call of the wild.” The boy who has been reared in a very poor home often is better able to take care of himself.”

In the files at the office of the Bureau of missing persons the records show that about 65 runaways were reported during one month. Two weeks later about one half of these had been located, and the cards telling the stories of these “dashes for freedom and adventure” conclude with the words “returned home.” This number includes local reports and those sent to the city from nearby towns.

Looking over these cards, it is possible to obtain an idea of those things which prove attractive to some growing boys.

One suggests that the runaway named may have entered the Navy or joined some show.

“She could be found around circuses,” is the statement on several of the cards, and on one it suggests that this particularly youth “may be found around shipping offices or radio stores,”

“Read wild West stories and talked about Army and Navy,” was interested in Marines or Navy,” “may enlist an army,” “was last seen in alto,” “was interested in movies,” our other inscriptions.

Other Data on Cards

The “movies,” however, are mentioned more often on cards recording the girl runaways.

On these cards are not only statements of the interest of the boy or girl who has disappeared but also usually a description of close worn when last seen and of any physical peculiarities as well.

The pathos of the unattainable may be read in the record of one girl, one whom it was stated that she might be found around motion picture studios and parlors, indicating that she had ambitions to become a movie “Queen.” But of whom it was also reported that she had a “splotched” complexion and was – sad to relate – “bow-legged!”

In the files may be found the names of boys and girls whose families occupy varied positions in the social scale. The name of the son of a prominent educator is filed next to a youngster whose training cannot have been conducted accordingly to very high standards. The fashionable girl who mysteriously disappears is in the same file with the girl who is, possibly, located on a “shore” and sent to a reformatory institution.

The traveler's aid society has its representatives at the railroad stations. There the stranded or perplexed man or woman, boy or girl, is approached and aid offered. The runaway is said to be recognized easily.

Recent Cases Tabulated

In its report for one month, there were 93 major cases recorded. Of these 25 were of persons less than 16 years old and 28 between the ages of 16 and 28.

The Bureau of missing persons recently compiled a report that will be read at the coming convention of policewomen to be held at Toronto, giving the number of female runaways and their ages reported to the Baltimore Bureau last year.

48 white and 25 Keller girls less than 14 years old were reported. Between 15 and 18 years, there were 117 white and 14 color girls; between 19 and 30 years the numbers were 68 white and 13 colored; and, after the age of 31, there were 29 white and 14 colored reported missing.

Of these numbers, 46 have not been located. The largest number of those whose disappearance remains a mystery is 17 between the ages of 19 and 30 years and 11 between the ages of 15 and 18 years.

Three Platoon System Will Start January 1

General Gaither Sets Date for Putting New Police Force Plan and Operation

To Ask For Funds in the Fall

Commissioner will appeal to the Board of estimates for funds for necessary equipment, including at least 30 motorcycles.

Police Commissioner Charles D Gaither has begun definite steps toward the establishment of a three platoon system for Baltimore’s police force. In less than six months’ time, the eight-hour tour of duty for Baltimore policeman will be in force.

It was learned yesterday the general Gaither is having a redraft made of the fixed posts. Officers competent for the work have been assigned to resurvey the police posts for the purpose of extending the lines. Many posts will be made larger. This will give an equal distribution of police service and will provide the necessary men for the three-platoon system.

Six Month’s Time Needed.

General Gaither is convinced that within six months the police force will be divided into three ships. The general said that, with the necessary equipment at hand, he will be able to put the three platoon system into operation January 1, 1921. The foundation for the system lies in recognizing the various posts. Work is now underway rearranging the new posts for the central district.

“I am quite positive that a better morale will be obtained throughout the department by instituting the three-platoon system.” Said Gen. Gaither.

“The city will get a straight eight-hour tour of duty from each of the three platoons. Foot policeman are necessary for certain sections of the city, but a mobile department can, in my judgment, render the most efficient service. The thing cannot be done in a day. But I expect to put this three platoon system into actual operation by January 1.”

Will You 30 Motorcycles

To execute this plan at least 30 motorcycles equipped the sidecars will be necessary. During the fall general, Gaither will go forward to the board of estimates and ask for sufficient funds for the necessary equipment. Within a few months, the personnel of the department may be up to its full quota, as it is believed men will be attracted to the department because of the new system.

Gaither Plans Details for Eight – Hour Shifts

Police Commissioner completing arrangements to put force on a three-platoon system.

Hampered, He Declares

Says Denial of Needed Motor Equipment Will Reduce Number of Reserve Patrolman

While police Commissioner Charles D Gaither will be unable to put the three platoon system of policing the city into effect January 1, he is completing details for the effective working of the eight-hour shift, he announced yesterday. 100 additional patrolman will be available soon, but the Commissioner Gaither says he realizes that it will take several weeks before these men are fit for active service. Post in all districts, except the northern and southwestern, has been remapped.

“I cannot fix any definite time when three platoon system will be put into effect,” said Commissioner Gaither.

“I intend to have the system in working order as soon as possible without sacrificing the general efficiency of the department. I have been somewhat hampered by denial of needed motor equipment and this will cut down my reserves. I planned to have a force of reserves, but the cutting down of the motor equipment has necessarily caused a reduction in the number of reserves.”

To Work Eight Hour Shifts.

The operation of the three platoon system means that policeman work a straight eight-hour shift. Hours of duty will be from 8 AM to 4 PM; 4 PM to midnight; midnight to 8 AM… the men will be divided into three divisions – first, second and third. The greatest number men will be assigned to the division on duty between 4 PM and 8 AM the divisions, according to the Commissioner Gaither’s plans, will alternate so as to eliminate men from Karen to annual assignment tonight work.

Commissioner Gaither has no authority to promote additional round Sgt.’s other than those provided by law. To provide round Sgt.’s for the new system he will be eligible to appoint 16 acting round Sgt.’s if he deems them necessary to the personnel of the division.

It was learned yesterday that in some instances the number of posts will be reduced in certain districts so as to provide men for the three ships system. To equalize the reduction of foot patrolman Gen. Gaither will strengthen the districts through the addition of motor patrols.

Plainclothes Forced Tripled.

For the past six weeks, the city has been under the heaviest police patrol in its history. The number of plainclothes policeman working from eight police stations has been tripled. The nucleus of this system was laid 13 months ago one Marshall Carter assigned 25 plainclothes men to the detective bureau.

Scores of suspected Negroes, mostly residents of other states, have been arrested during the past week, and the number of holdups reported is lessening

29 July 1920

The shakeup is Imminent in Police Department

District Captain slated for Transfers that may include Lieutenants and Sergeants

Gaither is silent on names

He says, however, that he has a plan to improve conditions retirement for detectives also said to be considered.

That a shakeup is imminent in the Police Department, the district captains are scheduled for transfers would probably will include lieutenants and sergeants. Was the information that leaked out last night at police headquarters? It also was learned that retirements are scheduled for the Detective Bureau and that a program for improving police service all over the line is under consideration.

Police Commissioner Charles D Gaither declined to discuss details of the impending transfers. Marshall Carter declared that he “was executing orders and was not in a position to discuss anything was general Gaither had underway.” Nearly everyone at police headquarters was equally uncommunicative about the reported shakeup, rumor of which was talked in corridors of the courthouse and on the street.

League may leave central.

It is known, however, the general Gaither now has under consideration the transfer of Capt. Albert L league central district. Capt. League has made several visits to headquarters during the last five days. It also was reported that Capt. George G Henry Northwest district is also on the slate for a change of command. Information concerning lower officers in the Department who may figure in the transfers could not be obtained, although a number of names were mentioned.

General Gaither declined to be quoted on the subject when names were mentioned. However, he did say this: “when I became head of the Police Department had one object in view and that was to give the citizens of the city the best police service possible. There is nothing authentic, at this time, in the matter of general transfers of men. I have a plan in mind for improving police conditions; if I believe captains may accomplish more efficient work to transfer, then, of course, the logical thing to do would be to make the change.”

During the two months that he has been police Commissioner, general Gaither has spent many days making investigations for himself. He has seen some things involving the Department of which he did not approve.

Hurley and Henry mentioned

The name of Capt. Charles E Hurley was mentioned last night as a Pro-bowl successor to Capt. League. As commander the northern district captain Hurley, it is said, has attracted the attention of general Gaither by the manner in which he has handled important cases. Hurley, it is said, can be counted upon for law enforcement in the central district, which may involve the sporting element. Capt. Henry, of the Northwest district, also is being considered for the central district assignment. It is not unlikely that Capt. Henry actually will be chosen to succeed Capt. League.

The names of two headquarters detectives have been mentioned in official circles for retirement. Both men according to police records have lost considerable time on account of illness and each has been a member the department for more than 30 years

16 October 1920

Tells How Prohibition Changes Police Work

General Gaither says The Passing of Salute has Caused Scattering of Criminals.

Explains Motorcycle Needed

Declares patrolman on foot is handicapped and that better protection would be given by a motorized unit

Police Commissioner Charles Gaither’s statement before the Board of estimates Thursday that the disappearance of the corner saloon has “so spread the troubles of the department” that a more mobile police force is absolutely necessary presented a new angle to the effect of prohibition on police administration that arouses interest yesterday.

Commissioner Gaither explained yesterday that he did not mean to imply that the elimination of the saloon has increased the work of the police, but merely that it has changed the nature of the work.

“With the neighborhood saloon in operation,” said the Commissioner, “the Police Department felt that, sooner or later, that saloon was a spot where trouble of some sort would likely break out. It was also, very frequently, a meeting place for men the police like to keep informed about. Because of these things the foot policeman was a necessity. He had to be kept in the neighborhoods and around such places as the saloons.”

“The elimination of the saloon, however, has changed all of this. Disreputable and suspicious characters will formally be gathered there are now scattered and a police must look far and wide for them. It is necessary, if these men are to be caught, they must be caught immediately after their crime has been committed. That brings the problem down to one of speed. The criminal of today doesn’t travel on foot or in streetcars. He uses an automobile.

“There is no need to keep a foot policeman now in one popular neighborhood. The size of our force compared with the size of the city means that it takes a man on foot about an hour to get over an ordinary beat in a residential section. The man who was going to commit a crime. Say a petty robbery for instance. Watches that foot policeman, season past the spot where a crime is to be committed, and then feel certain the policeman will not be back to that spot for an hour.

“With more motorcycles, however. We could do so much better. Taking for a post, as at present constituted, we could cover them all to men on foot and one on a motorcycle, and cover them better. The motorcycle man would be free to roam around the whole territory of the four post. The burger would never know when to expect him. He would pop up at any minute anywhere.

Besides, he continues, “we could establish motorcycle stations throughout the city, with a man always on duty at them. If a resident anywhere heard a suspicious noise or saw anything that needed the attention of police he or she could use a telephone and a motorcycle man would be on the job almost anywhere inside of five minutes.”

Here Wisdom of Baltimore Policemen Reads like some Bestsellers

15 August 1920

In 23 years 1078 Members of the Force received Commendations for Bravery and Self-Sacrifice and Devotion to Duty.

In 23 years 1070 policemen have been commended for heroism and good policeman ship on the Baltimore police force. They have been required to appear before the board of police commissioners and more recently before General Charles D Gaither, the sole Commissioner, to be gravely patted on the back and told that they were a credit to the force. Terse, formal letters have been written to them, and their names and acts have been printed on the lookout sheet which every policeman studies every day for tips to new cases.

Back to the formalities of these 1078 commendations are 1078 stories of intense human interest. Brought with all the thrills that must figure in detective novels, teaming with bravery, self-sacrifice, and mystery and screw deduction. In the thick file full of letters and reports that Sec. Josh Kenzie keeps locked up in police headquarters whole bestsellers are packed in single pages

All in a day’s work

Yet, for the policeman, it was all in a day’s work on the streets of Baltimore.

For instance in the midst of a shelf of letters from persons who solve patrolman Sidney Mercer stop a runaway horse on Howard Street four years ago there is this report from Mercer Robert D Carter Marshall Sir about 5 PM March 7, 1916 while I was on duty at Howard and Fayette Street I saw a horse attached to a wagon run south on Howard Street when the team reached Fayette Street and grabbed the bridle rein and stopped same one south side of Fayette Street by throwing the works no one injured the shift of the wagon and harness was broken that is Mercer’s report just as he wrote it punctuation and all. He had to make the report, every policeman has to make one about every incident that he believes worth a report. He would rather not have made it. Any policeman would rather not. Reports require writing and composition, and policeman are not notable writers.

If Mercer had been a notable writer and as much given to self-glorification as to hear his him he might have told how the horse had started to bowl at Franklin Street, how it was coming at East at top speed when he stepped in front of it from his traffic post, how he leaped and grabbed the bridle with both hands and flung his legs around the horse legs throwing it like a wrestler.

Didn’t Tell of Own Rescue.

But Mercer was like patrolman Henry Mager sip, of the Eastern district, who wrote, describing how he had taken part in a fire rescue just before he had to be rescued himself:

I was at my posted Baltimore next streets when I heard two shots, and running to Exeter and Pratt streets I went upstairs and was handed Mrs. Henry marvelous. I took her outside and handed her to a boy and went back upstairs.

Seven patrolman and two sergeants were recommended for rescue work at this Pratt Street fire. They were all going home on Roland Park car at 415 in the morning and a patrolman saw smoke coming from the door and windows. More children and to all persons were asleep on the second floor.

Sgt. Henry lineman kicked in the side door. The police informed the line from the top of the stairs to the bottom because the stairway was about 18 inches wide and they had to pass the half suffocated victims over their heads from hand-to-hand. When Mager sup and patrolman trolls am Davis got back to the street they heard that somebody was trapped on the third floor and started back.

Davis came down to gain gasping, and when he looked for Mager sup that policeman was missing. Peering upward to the smoke is all Mager sip hanging over the second-floor window sill he ran over to a fire truck, got a ladder with the help of some other policeman, and mounting it alone, carried the unconscious Mager sup to safety.

Caught 19 All Jacks

Four policemen were commended in July this year for rounding up 19 automobile themes in 10 days. They had stolen 43 automobiles. The policemen were Sgt. Thomas Burns and John Lynn patrolman Oscar M Cannon and show for James Feeley.

Nothing appears in their reports to show how they worked, but an idea may be gained of the way policeman Auto jacks from the story of how patrolman Robert E Bradley and George W Leon caught to them.

Coming down Lexington Street one night Bradley Saul two men near a car at liberty and Lexington. His policeman instincts made them see the car and men in one glance and he became alert. He hid behind another car to watch them. In 20 minutes a third man joined them. They did nothing but talk. Then they parted, to going west on Lexington Street.

Bradley followed these two by a devious route to center and Howard streets, picking up Leon on the way. At center and Howard, the policeman quietly collared them. Not a thing had they done so far as the policeman knew. They acted purely on instinct. But then they got the men back to headquarters the prisoners confessed not only to the theft of two cards, both of which were recovered but admittedly assaulting a man at Furnace Creek, a man who was still in the hospital. The Anna Bradley, by the way, were new men to the force

Highwayman Suit in Cell

It was instinct plus alertness that led to sergeants and three patrolmen to the Served for Highwayman just two hours after they had robbed a man on the street of his watch and pocketbook.

The robbery occurred at 1230 in the morning an alarm was sent around to all policeman. At 2:30 AM sergeants Cornelius carry and Charles Baker were strolling east on 25th St. near St. Paul, when they sought to soldiers crossing 25th at Calvert Street. Baker ran down St. Paul Street the 24th, aiming to box them in. Patrolman Walter Martin came up and carry sent in after Baker.

Next minute a soldier and a sailor came along St. Paul toward 25th St. and carry. Have been joined by patrolman George Will, grab them. At Calvert and 25th St.’s, they met Baker and Martin with two soldiers. And the whole bunch March to the station. The victim of the robbery identified all four.

Baltimore ends no more of the story of the burglars who robbed Stephen and/or wigs jewelry store in September 1916, then and these other cases. They were Jacob Kramer and Leon Miller notorious safe men with pictures and every bird Killian Bureau in the country. But they had become notorious by being masters of the crime, and their Baltimore job had been a fair exhibition of their skill. They had stolen $18,000 worth of jewelry and left not a clue. But the book of commendations holds two letters to detectives George Armstrong and Peter Bradley for Armstrong and Bradley got Kramer and Miller and put them away in the Maryland penitentiary for 10 years.

Doggedness, wariness, and self-control had won laurels for Armstrong and Bradley in this case. After trailing Kramer and Miller through Philadelphia and Boston, they stood one day in a railroad station in New York close enough to the two safecrackers to startle them with a whisper. But they let them go. They wanted to get them with the goods – and dream of every detective – and they did, that very night

Water holds no terror for them

It’s instants after instance of the everyday policeman in Baltimore that has one commendation where to be multiplied the stories would fill several newspaper pages. So only a few cases can be selected randomly. But it might be well to mention that Baltimore policeman has taken to the water in the line of duty, as patrolman Edward Healy, of the Eastern district it one day when he heard the cry, “Man overboard!”

Healy ran to Pratt Street and E. Falls Ave., and there was a man in the harbor, claiming to appoint of slippery rock while two men looked down at him helplessly. Patrolman Healy stalls a rowboat more about two blocks up ran their road down to the man, who was about to lose his grip, and got him into the boat. He lay on the floor, apparently half dead until the rowboat came but needs Pratt Street Bridge. When he jumped up and tried to leap overboard, he was drunk.

Healy had on a long winter overcoat. If he had to jump after the man he would’ve drowned. But he grappled with him, threw him to the bottom of the boat and for the best of the trip to assure used him for a seat while he paddled with one oar. The other had floated away with this couple.

Once Machine Guns and Rifles for Force

15 October 1920 Gaither, outline department needs, ask for new weapons to well riots.

Mobile force is his aim.

He proposes a wider use of motor equipment. Adequate reserve strengths and three platoon system – may do without a boat.

Rifles and machine guns for the use of the Baltimore police department were asked for yesterday by Commissioner Charles the Gaither, who was called before the Board of estimates to explain the financial needs of the department next year. He said his plan was to put the department in a better position to handle riots, and in urging the innovation, referred to the recent outbreaks among prisoners at the Maryland penitentiary.

Commissioner Gaither said the Police Department of New York, Boston, Philadelphia and other large cities were equipped with rifles and machine guns. He asked for two machine guns for the local department and $7000 for the purchase of rifles.

Mayor suggested an Alternative.

It would make of the Police Department a sort of trained military force that would be of benefit to the city when needed, the Commissioner pointed out. Mayor Broening suggested that federal or state troops might be asked for one such occasion, but Commissioner Gaither said the police would be quicker.

Outlining his plan for 1921, Commissioner Gaither said his aim was to raise the standard of the department and put it on a more efficient base by inaugurating the three platoon system, increase to 135 the number of men on motorcycles. Provide sergeants and others in outlying districts with automobiles, place inadequate reserve force in each police station and make the department a mobile force.

Can dispense with a new boat. City solicitor merchant told Commissioner Gaither that the board of estimates was hard hit this year and that it would be necessary to make cuts in all department estimates to keep the new tax rate within reasonable bounds. The Commissioner promised his hearty cooperation in keeping down the expenses, and in this connection said his department would not be crippled if not given the new police boat next year for which $75,000 was asked. He also stated that he could, if necessary, get along without new patrol wagons that were asked for.

The board showed a disposition to eliminate from the police budget provision for the boat and patrol wagons, and one or two other small items, thereby cutting nearly 2 cents out of the tax rate.

The general discussion developed the intention of the board to strip the department budget of all but actual necessities.

Would Buy Men’s Uniforms

With the possible exception of the new boat. The patrol wagons and other improvements not considered absolutely necessary at this time. Commissioner Gaither will get what he asked for in his budget, which shows a total increase of $414,000 compares with the appropriation for 1920.

Without including it in his budget the commission recommended an appropriation of $50,000 for the purchase next year of uniforms for new man coming into the department and for replacing and repairing uniforms of those already in service.

Commissioner Gaither said a uniform including overcoat, cost the policeman $105, under the terms of the existing contract. Attention was drawn to the fact that the policeman of Baltimore received less pay than those of other cities, and that it would be no more than fair to give them their uniforms. The board of estimates to the matter under consideration. 100 more men needed, he says.

Explaining the increase in his budget Commissioner Gaither said the $130,000 was for 100 additional policemen next year. He said they were absolutely necessary and pointed to the fact that Boston has 900 more policemen than Baltimore. The additional motorcycles the department wants will cost $111,508 speaking of this plan for placing more men on motorcycles, the Commissioner made a point of the fact that the disappearance of the corner saloon. Which required the presence of a policeman in the immediate neighborhood, has so spread the troubles of the department that policeman must now look after burglars and other miscreants in scattered sections.

The present method of policing is based on footwork, the Commissioner asserted, and there is not a post a man can walk around in an hour. The Commissioner went on to say that without the three platoon system the city will be without the protection it needs. Post now covered by four men will be covered by one footman and two motorcycle men, Commissioner Gaither said.

Would increase reserve.

Urging the necessity for more motorcycle men, Commissioner Gaither said it would enable him to have a reserve force of eight men at each station at the present time, he stated, the reserve is on the street and must be picked up in emergencies.

Under the new system each district will have a fixed post, which will enable persons needing a policeman to get him in five minutes, at most, Commissioner Gaither said.

Increasing in salaries, including the pay of the 100 additional policeman totals $209,263.40

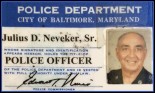

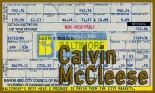

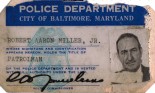

NOTICE

How to Dispose of Old Police Items

If you come into possession of Police items from an Estate or Death of a Police Officer Family Member and do not know how to properly dispose of these items please contact: Retired Detective Ken Driscoll - Please dispose of POLICE Items: Badges, Guns, Uniforms, Documents, PROPERLY so they won’t be used IMPROPERLY. Please contact Det. Ret. Kenny Driscoll if you have any pictures of you or your family members and wish them remembered here on this tribute site to Honor the fine men and women who have served with Honor and Distinction at the Baltimore Police Department. Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. follow us on Twitter @BaltoPoliceHist or like us on Facebook or mail pics to 8138 Dundalk Ave. Baltimore Md. 21222

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History - Ret Det Kenny Driscoll

English (UK)

English (UK)

.jpg)

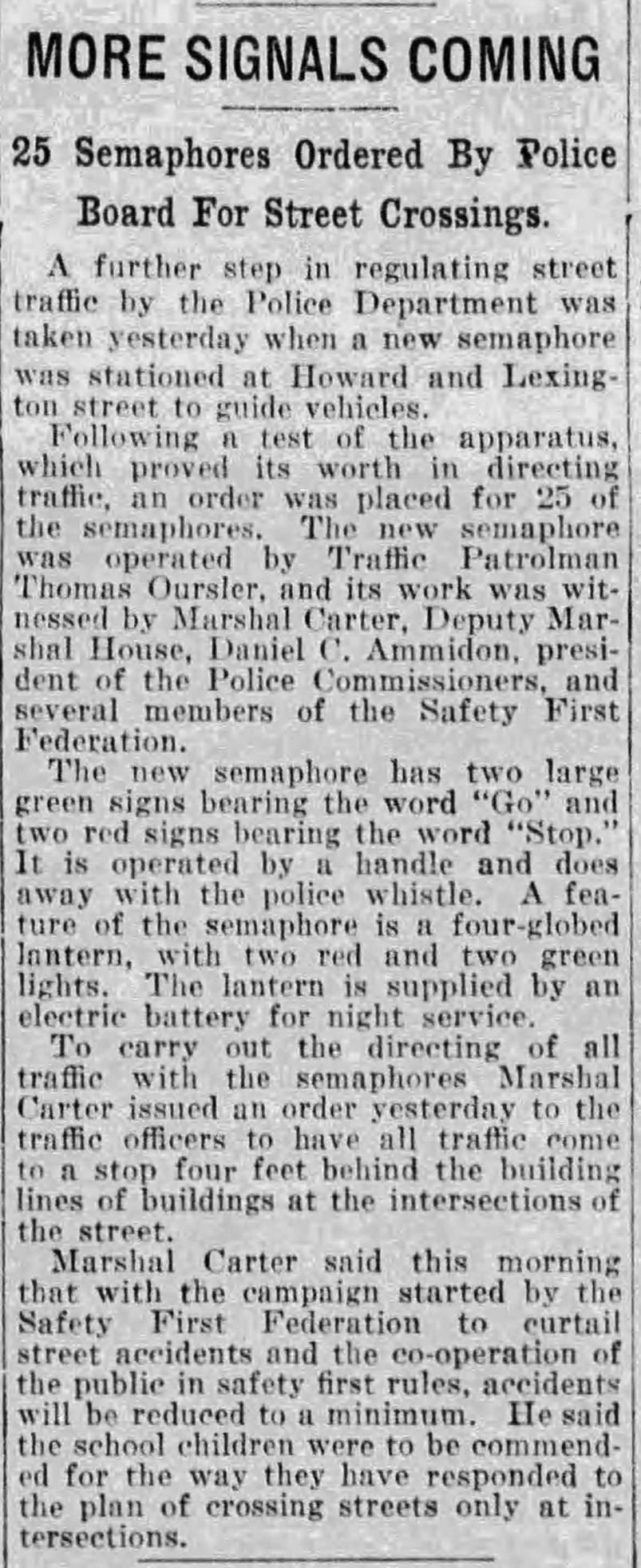

1920 Semaphore

1920 Semaphore

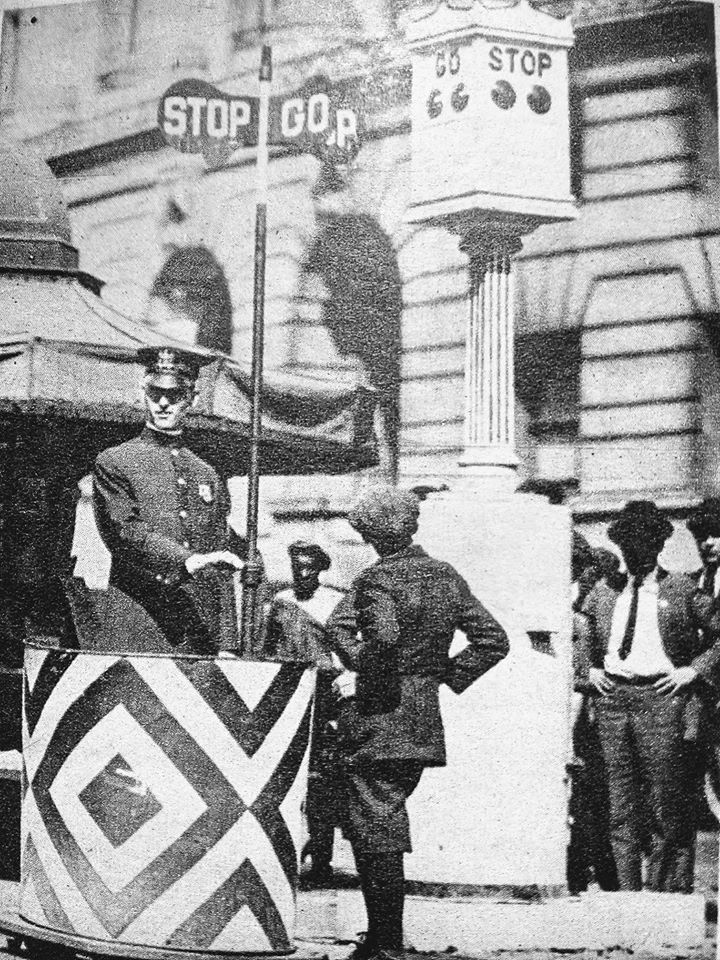

Traffic booth and Officers directing traffic at Liberty and Lexington Streets

Traffic booth and Officers directing traffic at Liberty and Lexington Streets